“People have asked me why I chose to be a dancer. I did not choose. I was chosen to be a dancer, and with that, you live all your life. ”

Martha Graham, Blood Memory (1991)

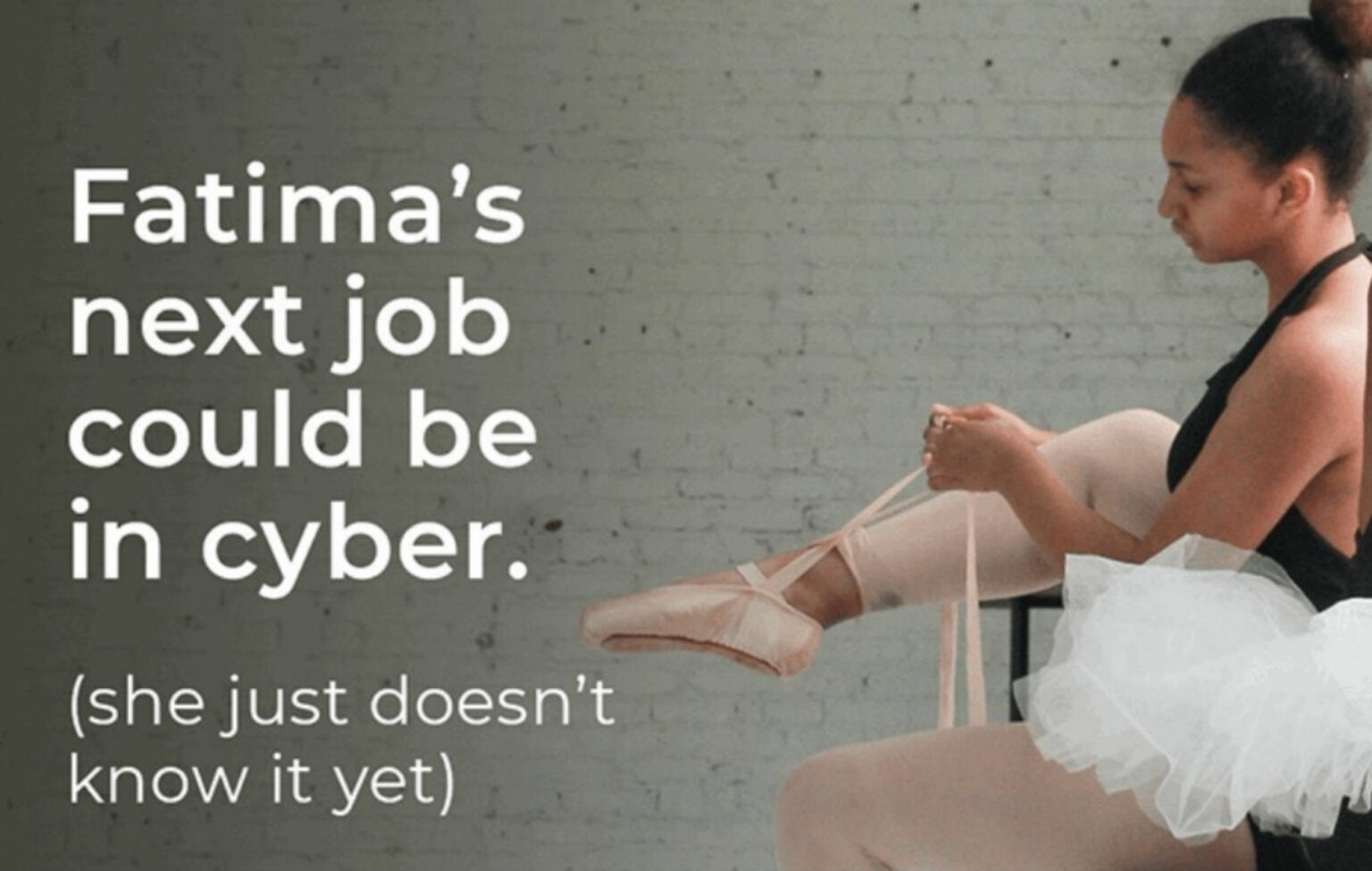

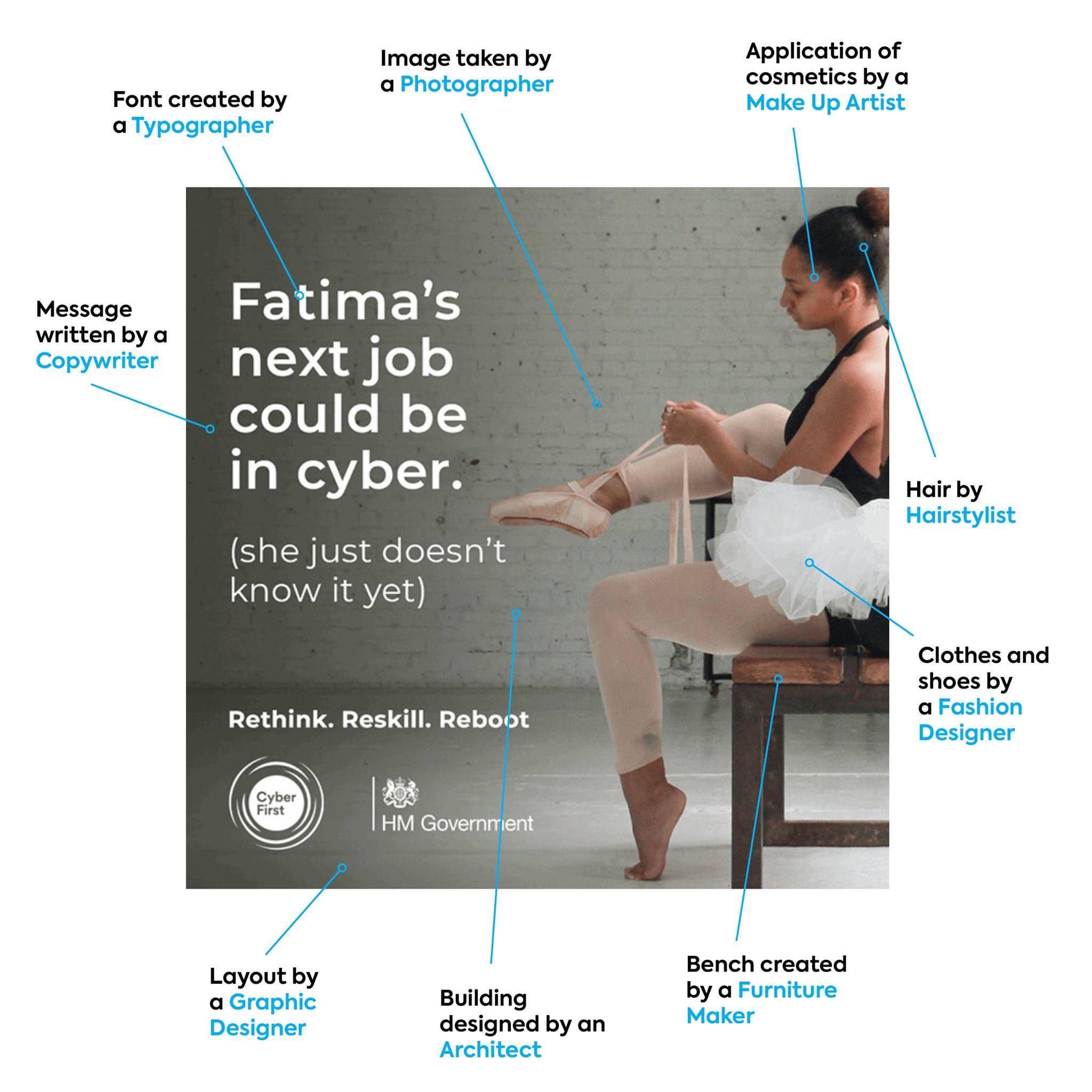

On the morning of October 12th , the day the first round of grants from the Culture Recovery Fund were to be announced, the airwaves started buzzing with a different story. An advert with a particularly unfortunate message. It showed a Black ballet dancer with the caption:

“Fatima’s next job could be in cyber (she just doesn’t know it yet).

Rethink. Reskill. Reboot”

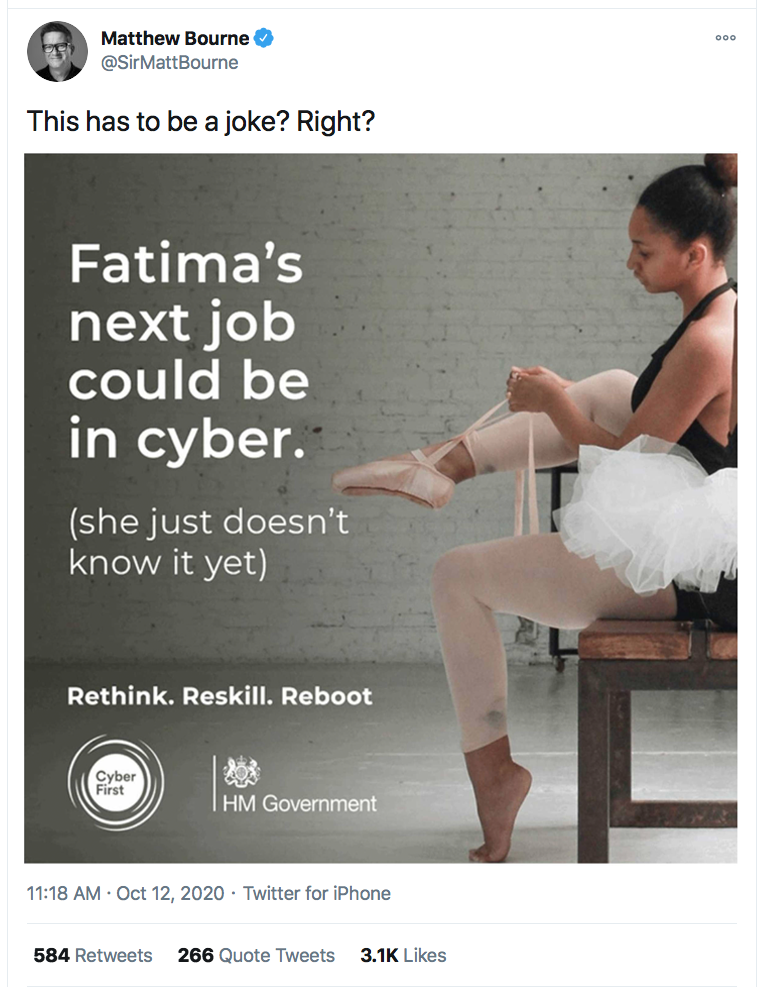

Cue large-scale creative incredulity and meltdown from some pretty big figures in the industry. This was from legendary choreographer Sir Matthew Bourne:

But it wasn’t a joke. The ad turned out to be from 2019, one of a series from CyberFirst, a government programme helping young people to explore careers in tech and cyber security. It was aimed at those in other industries. Perhaps it seemed like a good idea at the time. But during a pandemic and at a time of creative paralysis, there’s no doubt that it resurfaced at the worst possible moment.

The week before, a tweet from ITV announced that in an interview with ITV News Chancellor Rishi Sunak had suggested struggling artists should retrain. Sunak later insisted that he was speaking about employment generally when he said “I can’t pretend that everyone can do exactly the same job that they were doing at the beginning of this crisis.” ITV deleted the tweet. Watch the interview and see what you think the Chancellor was saying.

If it is a misunderstanding, you can certainly see where it came from. In mid-September, Sunak had announced a wage top-up scheme that would protect “viable jobs”. Step forward all those with a viable job! Writers, actors, dancers, musicians, composers, creatives: not so fast. Because the wage top-up could only be claimed by employees working a third of their usual hours, industries still in shutdown or unable to employ workers over the coming months wouldn’t receive any support.

Given the timing, and the huge holes in the SEISS scheme that many self-employed creatives have been falling through, it was hard not to see the advert as government pressure on young people to “rethink” their unviable careers in the arts. As David Mitchell pointed out in his Observer column,

“…it is not just a bad advertisement, its badness has reached a point of delightful perfection. Within the parameters of its aims, it absolutely could not be worse. It’s trying to make the point that, at this difficult time, people might want or need to change careers, and to suggest cybersecurity as an option. That’s a hard sell to begin with: cybersecurity sounds boring and malevolent. But the choice of a ballet dancer as a person who might be drawn into it is so inexplicably, idiotically poor that it becomes something comically amazing.

I can’t think of a job where a higher percentage of the people involved have chosen to do it, deliberately and passionately, than ballet dancer. Nobody “ends up” doing ballet. They don’t knock around in their early 20s and then somehow find themselves in a ballet. You don’t get stuck in a ballet rut. It is a job done exclusively by people who have dreamed of doing it for years, and then striven against the odds to make that happen.

It’s not an imperfect choice of image for the campaign, it’s the worst imaginable choice. It is a spectacularly bad mistake. It is like using petrol instead of water or cheese instead of steel.”

Where Fatima really needed to be was on stage. But 2020 has seen live performance in a fight for its very existence. For the last decade, the sector has done all that was asked to wean itself off subsidy, which has been slashed. As we pointed out in our last edition of the Arts Index, a decade of arts cuts has left organisations almost entirely dependent on income generated from ticket sales, venue hire, drinks and food; this earned income is up 37% since 2010. Most UK venues with producing companies now earn about 85% of their running costs and get 15% or less in government investment. On the continent, the figures are reversed. Theatres and concert halls are supported for three-quarters of their income and only have to find a quarter from ticket sales.

Of course these are long-standing inequalities, but ten years of cuts (the Treasury arts budget is now two-thirds of what it was in 2010) have made them much worse. Doing the very thing the sector was asked to do is what has brought it to its knees. Having to play to 80 – 90% to break even, socially distanced seasons (which started months ago elsewhere in Europe) are now impossible to budget for profitably.

In contrast, federal culture spending in Germany is €1.8bn annually. Monika Grütters, Minister for Culture and the Media, who oversaw an increase in the budget for federal cultural affairs of more than 30% between 2013 and 2018, was quick to reassure the country in March that “artists are not only indispensable, but also vital, especially now”.

It’s this last vocal vote of confidence that is missing in the UK. Nobody in government is calling artists indispensable, either as generators of GDP or makers of work that keeps people sane and happy. As freelancers, we weren’t eligible for the furlough scheme. Nobody seemed to be taking seriously the fact that retraining was a disaster for most people. Artists felt ignored, undervalued and misunderstood. And the advert just summed it all up.

Grace Molony, the leading actress in my production of The Watsons, which was due to have a twenty-week West End run in 2020 and was cancelled in April, is now working as a teacher’s assistant. Good for her; it’s wonderful that the teaching profession has the help of such a clever and empathetic person. But last year Grace was nominated for the Evening Standard Emerging Talent Award for her performance. She’s really really good at acting. And we can’t afford to lose her. She should be leading a West End company in a successful run, making money for the UK through ticket sales.

To say Fatima backfired is an understatement. But she also bred dozens of responses that were beautifully on point. The sector did what it does so well: producing in a matter of hours columns, videos, comics, poems, songs, and dozens of parodic adverts, from Shakespeare (“William’s next job could be in an Amazon warehouse. He just doesn’t know it yet) to Baroness Harding (“Dido’s next job shouldn’t be in cyber or healthcare. But they’ll give it to her anyway.”)

In a tweet, writer Caitlin Moran wondered about the new government “Hopes and Dreams Crushing Department”:

Michael Spicer made a TikTok video which had fun with the fact that most people don’t really know what ‘cyber’ is.

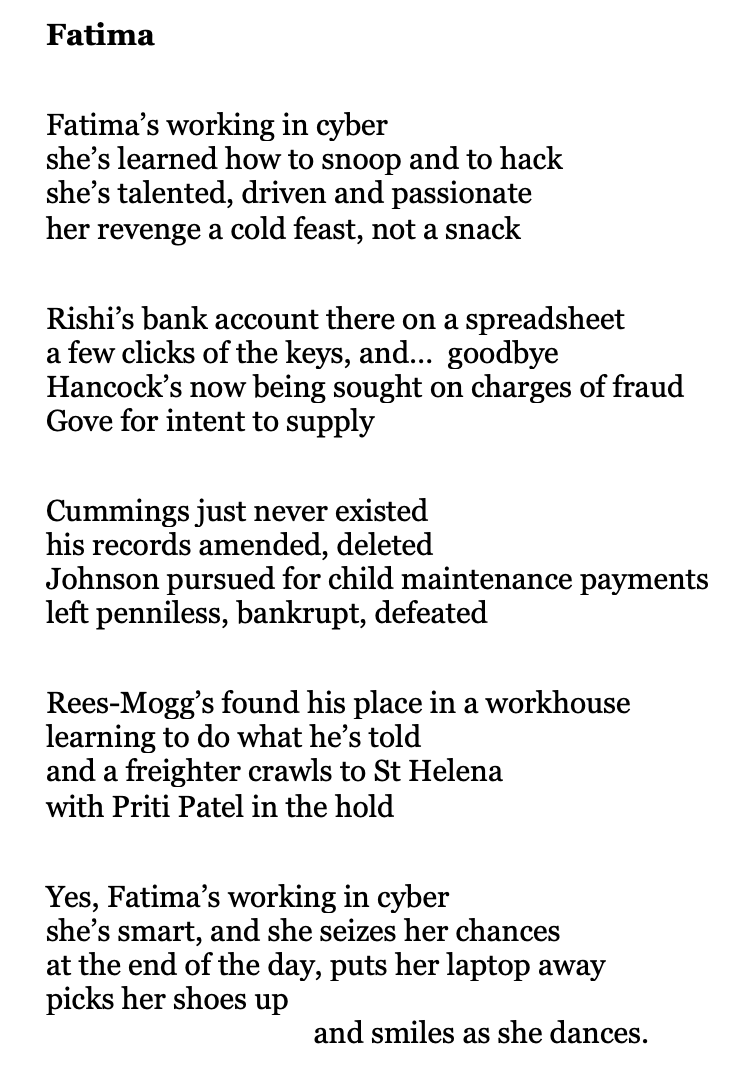

Poet Steve Pottinger quickly composed this poem:

Pottinger was delighted when his poem went viral and was even set to music by the Flemish singer An Croenen Brutsaert. He said on his website:

“Watching this government flail around from one bungling catastrophe to the next – while failing to look after the people it’s supposed to serve – it can be easy to feel isolated, despairing. I believe that art, satire, humour, and righteous rage can do a lot to lift that gloom. It seems a lot of other people feel the same. And that will always give me hope.”

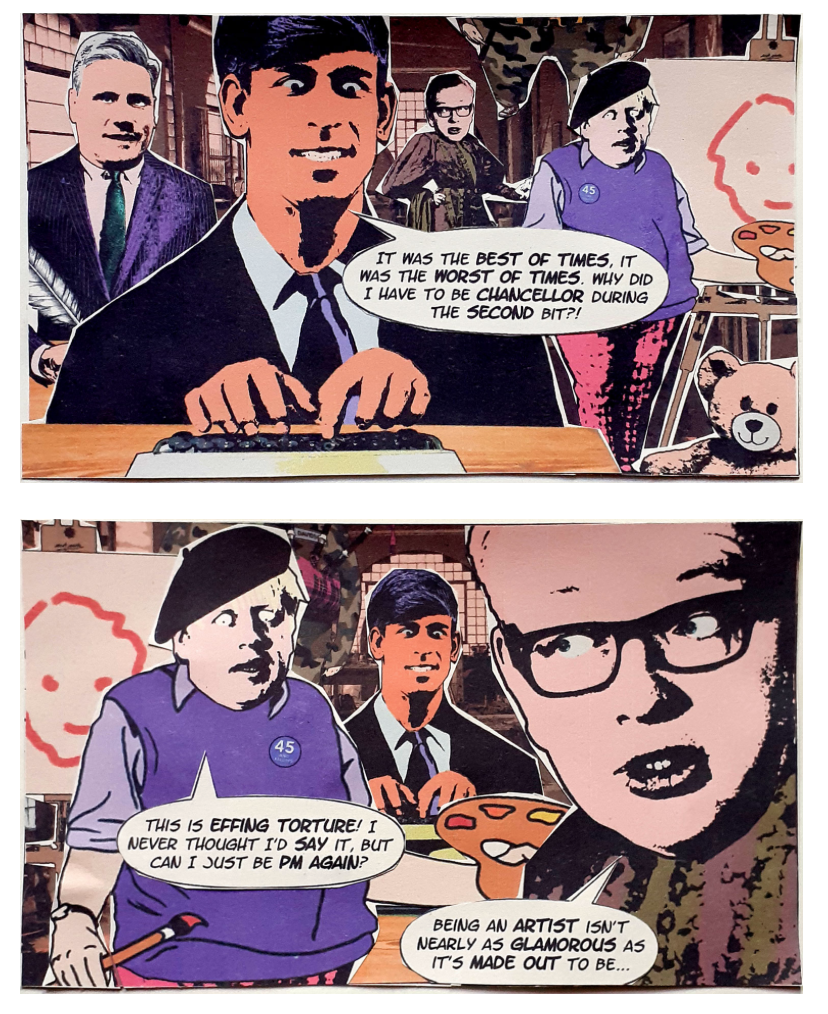

The artist Greg Moodie produced a comic called If Politicians Were Artists, proving that art wasn’t as easy as they all thought:

And on Instagram, designer Sean Coleman pointed out how many creative jobs were involved in producing even the worst advertisements:

These parodies and commentaries were silver linings in a very dark cloud. The choice of a Black ballerina seemed especially crass. Black ballet dancers are hugely underrepresented in mainstream ballet (the company Ballet Black was founded by Cassa Pancho in 2001 for exactly that reason). Until 2016, ballet shoes weren’t available in Black skin tones. Almost by definition, a ballerina has spent her every waking moment since childhood living and breathing dance. Training, practicing, trying to grow and nurture her talent until like a vanishingly small number of those who dance she actually manages to turn professional, avoid injury and make a career in a hugely competitive field with high burnout and turnover. I’m reminded of the character of Imogen Hassall in Terry Johnson’s Cleo, Camping, Emmanuelle and Dick, who trained at ballet school and ended up in Carry On films, complaining that she was better known for her curves than her talent:

“What I’m saying is, I’m not just some stupid girl from Elmhurst with a fucked knee.”

A campaign that understood what artists were going through might have used a slogan like “We love what you do. We know you’ve worked hard at it. We’re working just as hard to #SaveTheArts.” Even if it weren’t true, the government would at least sound like they were on the same planet.

Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden quickly denounced the ad, calling it “crass” and that afternoon (October 13th) it was quietly withdrawn. Questioned the next day by the House of Commons culture select committee, Dowden was careful to show his support. “I was at the Royal Ballet just on Friday and it was wonderful to see artists perform again…We know those are jobs that should be preserved”, he said.

But the damage was done. Even though it came from a different department, the advert had HM Government’s name on it; someone must have approved it, and that was enough.

The storm was very disturbing for the photographer and subject of the original picture. Krys Alex, a Black American photographer who took the photo in 2017, described Desire’e Kelley as “a young talented and beautiful aspiring dancer from Atlanta, who has dreams of attending college to study dance.”

The uncropped photograph also shows Tasha Williams, the owner of the dance studio Vibez in Motion in Fayetteville near Atlanta, where it was taken. When the story broke, said Alex, she thought about Tasha. “She has been dedicating her life to the arts and helping young people and children like Desire’e pursue their dreams and their careers as artists.”

“I understand the controversy,” said Alex. “I can relate as an independent artist in the creative community. The pandemic really hit us hard. It’s not easy to find work. Especially being a black woman with all the current racial injustice going on. I feel like artists should stand together and support each other. Our hard work deserves to be recognised. We should not be encouraged to stop doing what we love.”

It was particularly unfortunate that the advert surfaced on the day the government were looking for happy feedback from those the Cultural Recovery Fund had been able to help. Staff at the DCMS and Arts Council were exhausted, following the distribution of £200m in emergency public funding and then the first part of £1.57bn from the CRF. The CRF is intended to stabilise organisations, protect jobs and help work flow to freelancers (see elsewhere in this month’s newsletter for interviews with three NCA trustees whose organisations received CRF support).

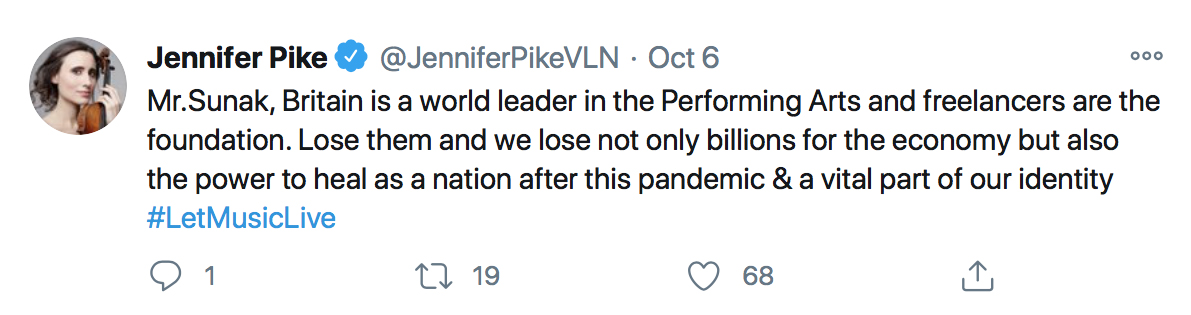

The creative industries bring £110bn a year to the UK economy, employing an estimated 3.2m people. The performing arts are a big part of that. During the September protests by self-employed musicians who felt they were being called ‘unviable’, violinist Jennifer Pike tweeted:

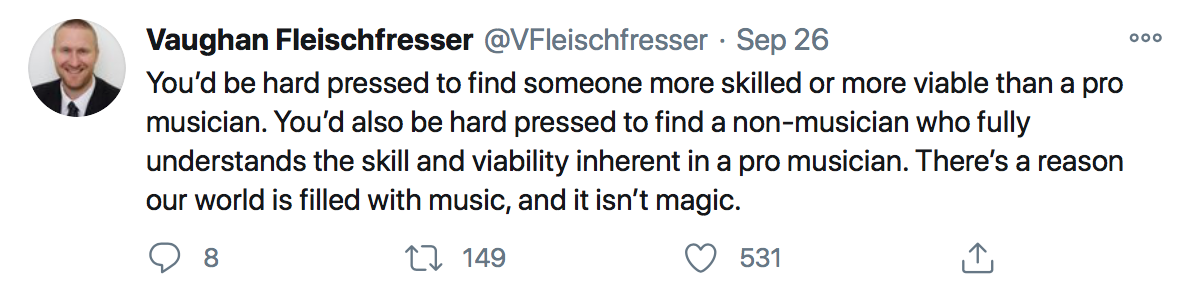

Conductor and music education advocate, Vaughan Fleischfresser pointed out:

Perhaps most surprising is the suggestion that people in creative professions haven’t already considered the possibility of taking on a second job. Many arts workers already have multiple jobs. The whole idea of a portfolio career, of ‘side hustles‘ and ‘slashies‘, is now closely associated with cultural and creative work.

People whose main job is in music and the performing arts are particularly likely to have a second job: actors, entertainers, presenters, artists (about 8%) photographers, audio-visual and broadcasting operators (10%) and, above all, musicians (11%); findings are from this report from the NESTA Policy & Evidence Centre. The majority of second jobs are not in creative occupations (80%) and are for the most part non-professional (60%).

Ultimately it’s the failure of imagination behind Fatima that grates. Whether it’s art, dance, music, theatre – for professionals it’s not a hobby. There seems to be no attempt to understand what a life dedicated to performing takes.

Am I being oversensitive? The advert may have been crass and dreadfully timed, but surely not deliberately so? I’ve chosen to go into this much detail partly because I really enjoyed some of the creative responses and partly because I think Fatima sits at the tip of a dangerous iceberg. It often feels that creatives in the UK today are not understood, not listened to, not valued. On the same day the advert was withdrawn, the National Society for Education in Art and Design announced that subject bursaries for training PGCE art and design teachers would not be renewed next year.

“For the first time, this year only (2020-21), our subject trainees were awarded a bursary”, they said. “Today, the DfE has announced, no bursary will be given for art and design trainees applying to join the profession and train 2021-22.”

As I write, Amazon has released its Christmas advert, about a young Black ballerina whose star performance is cancelled because of COVID. Her family and friends make it happen anyway, on a snow-dappled carpark while neighbours watch and applaud. It’s beautifully done. The soundtrack is a soaring string version of Queen’s The Show Must Go On. Amen to that. It’s just a shame that in real life the ballerina concerned is now retraining in cyber.